| Murals |

| Introduction |

| Seven Lively Arts |

| Story of Oil |

| Communication |

| Chronology |

|

CHANGING VISION |

|||

|

|||

|

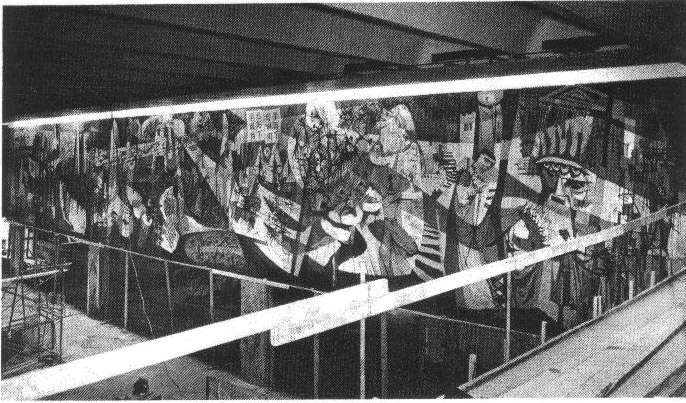

Now, thanks to a recent cleaning, Wilson's work has been restored to its former glory. With 26 years' worth of dirt and grime removed, the mural sparkles once again. It's easy to see why his contemporaries considered Wilson Canada's leading colorist. But no work of art ever had a harder birth. It was notorious long before it was completed. It made headlines as far away as London, England. At issue was the survival of artistic freedom in the face of union demands. Because the O'Keefe Centre was still a construction site, the International Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers of America decided that Wilson had better sign up. He refused. The union threatened a work stoppage. The fight was on... But in September, 1958, when the story began, no one could have foreseen such an outcome. O'Keefe had just formed a committee whose task was to select an artist to create "the largest mural ever undertaken in Canada." The huge work, measuring 100 feet by 15 feet, was to be "the focal highlight of the lobby of the O'Keefe Centre," then still under construction. The committee, which included Martin Baldwin, director of the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario) A.J. Casson, last living member of the Group of Seven, and Charles Comfort, was also entrusted with approving the final design of the monumental work. "This mural is not a piece of decoration," Casson said at the time, "but an important contribution to Canadian art. It will present the artist with many challenges never before encountered in executing a mural in Canada." Casson couldn't have known just how prophetic his words would be. On November 20, 1958, the committee announced that Wilson had been chosen. the decision made a lot of sense. Wilson was exhibiting his paintings internationally and had completed several successful murals, most notably the Redpath Library at McGill University in Montreal and the Salvation Army headquarters and the Imperial Oil Building here in Toronto. True to form, Wilson set to work by producing an extended series of preparatory sketches. Though they are a far cry from the finished project, these sketches have a life all their own. Even the most casual, done in ink on newspaper, have a vitality that transcends their humble origins. The result of this year-long process was a semi-abstract celebration of culture. Titled "The Seven Lively Arts", Wilson's mural depicted dance, drama, painting, sculpture, literature, music and architecture. The piece, which exemplifies Wilson's ability to balance realism and abstraction, was thoroughly modem. It contained many historical references but the overall feeling was one of energy and movement. Not only did it identify the purpose of the centre, it humanized the surroundings. Best of all, perhaps, the mural is a statement of its time. |

|||

|

|||

|

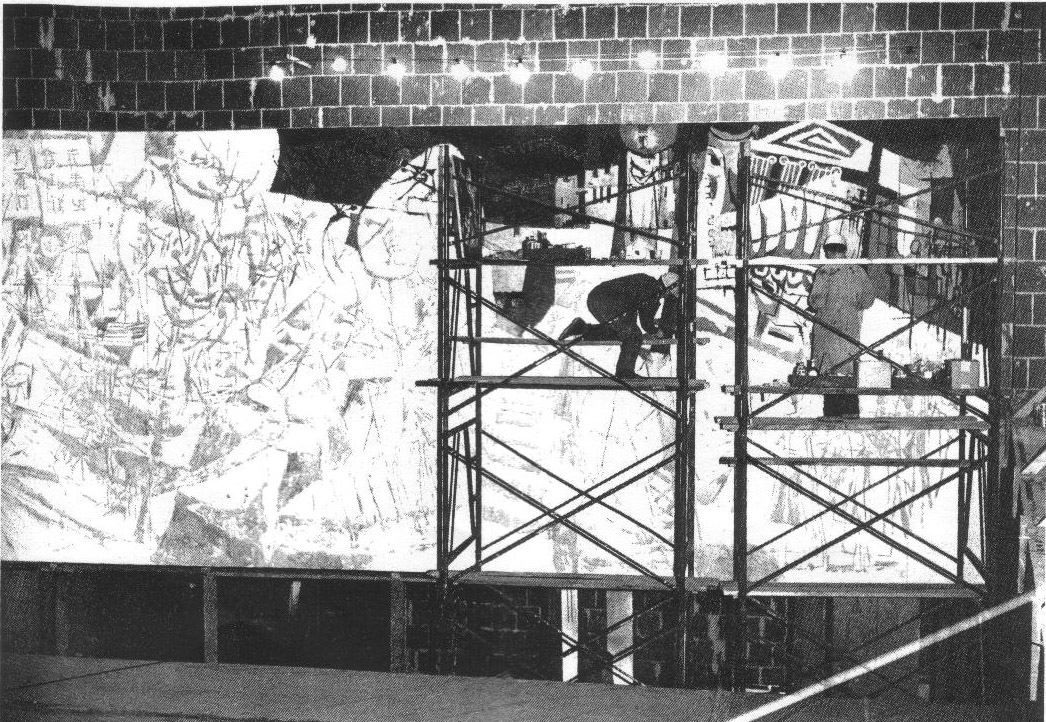

So was its making. If things started quietly, they soon got loud. Shortly after Wilson had begun work on the mural with two assistants, Bob Paterson and John Labonte-Smith, then students at the Ontario College of Art, they were approached by members of the Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators and Paperhangers of America. They demanded that Wilson and his helpers join the union. The mural, they argued, came under the union's jurisdiction, which included stage murals, scenery and costume design. As the delegation from the union also pointed out, the three artists were the only workers on the site who didn't belong to a union.

"R. York Wilson International Brotherhood of Painters Decorators & Paper Hangers" Comic Strip by Grassick of The Telegram, Toronto, Wed., Jan 20, 1960 By mid-December, representatives of the union, O'Keefe Centre and O'Keefe Breweries were holding talks on the issue. The union officially demanded that the mural be painted by its members. "We have served notice that we want the mural finished by persons carrying a union card," said Harry Colnett, Canadian vice-president of the union. Failure to comply, it was strongly hinted, would lead to a walk-out and/or picketing of the building site. For his part, Wilson refused adamantly to have anything to do with the union. He considered the whole episode "absurd" but had to fight to affirm his position that an artist must remain independent. Indeed, Wilson went on record as saying he would finish the mural without the union even if it meant he had to do it alone. In January, 1960, Wilson and the union reached an uneasy peace. The union would withdraw its demand that he join. In return, Wilson would complete the work by himself; the artist might be exempt from union claims, but not his helpers. Under pressure, both had left. Wilson, however, was not happy with the arrangement. He was a 53 year-old man who had suffered a heart attack only three years before. "I have been advised by my doctor, W.F. Greenwood," he wrote in a statement, "that I am not in good enough physical condition to complete the mural by myself. For these reasons," he continued, "I have no alternative but to follow the advice of my legal adviser..." Wilson's lawyer, George Ferguson, sat down with the union and hammered out an agreement. The union finally conceded Wilson's right to complete the mural without joining the union. |

|||

|

Wilson had won. He had asserted the independence of the artist. But it was a costly victory. The leading arts groups of the day rallied to his support. The Royal Canadian Academy, the Ontario Society of artists, the Canadian Group of Painters and the Sculpture Society of Canada pooled their resources and paid half the lawyer's fees. Wilson also received legal advice from the late Bora Laskin, who later became chief justice of the Supreme Court of Canada. |

|

||

|

Word of the dispute, and of Wilson's triumph, spread. The Times of London ran an editorial hailing Wilson as the first man to challenge the guild since the 17th century. Wilson's wife remembers the experience vividly. "It was very frightening," she says simply. "We were getting threatening phone calls saying York might have an accident on the scaffolding or something. At one point Bora told us to disappear for awhile." They did, for three days. But when the mural was at last unveiled in May, 1960, it was a hit. Like Wilson's other large works, it soon became part of the fabric of the city. Though we may tend to take it for granted, the O'Keefe piece is a spectacular example of the art of the 1950s. Wilson was working in a style that might be termed decorative cubism. Though the mural has many abstract elements, it also contains a high degree of realism. The references are never obscure or hard to make out. In the architecture section, for instance, we see a clear representation of the Parthenon. In the painting section, Wilson added figures taken from the hieroglyphics of ancient Egypt. Again, there is no difficulty making them out. In some areas of the mural, however, Wilson was less straightforward. Perhaps because it depicts movement, his portrayal of dance is the most abstract of the mural. The swirling men and women it portrays, their arms and legs wildly extended, seem to come right off the surface. As O'Keefe general manager Charles Cutts puts it: "In addition to adding class and elegance to the lobby, it really makes a statement on its own." Cutts also plans to improve the lighting of the mural. The trick is to devise a way of increasing the brightness without making it hotter. The process is complex but it should be in place sometime next year. For Diane Falvey, the Toronto conservator who supervised the recent cleaning of the mural, the lighting will be the finishing touch. She and an army of 20 helpers spent four days, 6 a.m. to midnight, washing the work with cotton swabs. "We removed tons of dirt," she says. "All of it brown and ugly." The difference was immediately noticeable. "I remember standing in the darkened lobby just after we'd finished and the colors seemed to glow," she recalls. "It was a really strange experience." What impressed Falvey, who by virtue of her profession is a technically minded person, was how well Wilson chose his materials. "He made his own paint," she explains, "using a special type of polyvinyl acetate (PVA)." According to Falvey, PVAs are desirable because they're "highly stable" and "color permanent." Wilson, she says, "was ahead of his time in his choice of material." As a result, the mural should be around for many years to come. Perhaps now that it has been renewed, it will once again be recognized as one of Toronto's most beloved artistic landmarks. Christopher Hume is art critic for the Toronto Star. "Changing Vision" first appeared in the February 1987 issue of COC Magazine, the newsletter of the Canadian Opera Company. |

|||

|

| Home | About This Site | Art Database | Search Site | | Biography | Exhibitions | Murals | Collections | Video Archives | Endowment Fund |